“Remember that your nations measure you by what you create and not by what you destroy.”

What to do about the growing number of disappearing journalists, the escalating violence towards environmentalist activists, or concerned citizens who dare to speak up about pipelines going through their sacred grounds, or about their disappearing butterflies or virgin forests, and now #BlackLivesMatter protestors risking life and limb for social change. Is there a way for humanity to survive and thrive and even leap up to the next level of co-creation instead of fighting violence with yet more violence? And what to do about “Silence gives consent”? How can we actively contribute without becoming yet another statistic? Or without stooping down to the same level as the perpetrators of violence? Or instead of numbing out and flicking to the next channel? (Question I’ve asked myself for decades.) This article explores two ways each of us can take positive action to ensure a better world for ourselves and future generations.

About a year ago I watched a youtube video of Jordan Peterson giving a talk on his 12 Rules for Life, an antidote to chaos. (Petersen is a highly controversial figure and I’ve been advised to cut him out of this story as he isn’t really relevant to what I’m writing about here. Maybe I will in future, in a shorter version of this piece, but for now I’m leaving him in so you can follow how I got to re-discovering Solzhenitsyn.) This video (which you don’t need to watch) led me to getting his book by the same title (which you don’t need to read) plus a copy of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s “Experiment in Literary Investigation: The Gulag Archipelago” which Peterson mentioned while discussing the 8th rule in his book, which is Always tell the truth, or at least don’t lie. (This part, inspired by Solzhenitsyn, is about 56 min into his video.)

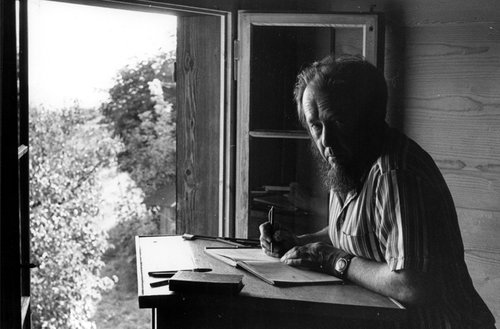

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in Sternenberg, Switzerland Summer of 1974. Solzhenitsyn Center

This incredible speech, written 50 years ago, feels like it was written for us now, as a call to action.

The truth of it rings in my ears but still I feel frozen. What to do?

I feel a strong affinity towards Solzhenitsyn because, after he was expelled

from Russia, he spent a few months of 1974 hiding out in the hills above Zurich, in a remote rural farm cottage in Sternenberg, belonging to a fellow writer and historian, the then mayor of Zurich, Sigmund Widmer. We moved to this region three decades after Solzhenitsyn’s brief stay, but still his spirit lingers here. As I write this, I can see his old rooftop peeking through the forest on the next hill across the valley. It feels as if he’s gently reminding me to read more of him, follow his guidance, put my head down and do my bit. His books are enormous volumes, each nearly as wide as they are high, and quite daunting just for that fact, never mind what’s in them, taking us to places we wish to never visit in this lifetime nor in any parallel or future lifetime either. And yet his work is about the ascent of the human spirit against all odds.

Solzhenitsyn needs to be read now, least we find ourselves going down the same slippery totalitarian slopes he and his countrymen explored during the last century. Solzhenitsyn’s epithany, after a decade in hell, was to connect the dots backwards to how seemingly petty lies and deceit about one’s own life, due to a desire to fit in or survive, lead to bigger lies and eventually participation in, compliance or turning a blind eye to massive crime against humanity and our planet. This process of decay and how it happens is really something for us to look at both individually and collectively, irrespective of ideology (which itself is another danger that he points to and thoroughly dissects).

In his Nobel prize acceptance speech, after he winning the Literature award in 1970 for the novel “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich“, Solzhenitsyn lays out two ways we can each take positive action whoever, or wherever, we are in the world.

- Firstly to look inwards, to observe and then clean up our own “fake news” or petty lies and deceits or bigger transgressions and participation in lies

- and secondly, to allow whatever creative inspiration we’ve received as a gift that’s attempting to work through us to come forth despite all odds and be a force of good. To use our craft to make the truth indisputable and to help others rise instead of sink, by sharing our own personal experience in a way that gives others a direct experience across space or time and thereby perhaps able to make the next big leap rather than go all the way into hell too.

I personally found it useful to access Solzhenitsyn’s thinking though Peterson’s pre-digested material because Peterson shares his own personal stories about attempting to tell the truth and stay in integrity and also because he ingeniously put the guts of Solzhenitsyn message, an essential call to action, onto the first page of the forward he wrote for the abridged edition of Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago. By presenting us upfront with a well chosen extract from Solzhenitsyn’s Nobel Prize for Literature acceptance speech, he manages to condense Solzhenitsyn’s vast body of work into a bite-sized meme for today’s easily distracted audience. This extract touched me so deeply I’m still pondering Solzhenitsyn’s words and wondering and experimenting with how I can apply these principles in my own life.

Here’s a small part of this extract from Solzhenitsyn’s Nobel speech so you can get a taste:

“Once we have taken up the word, it is thereafter impossible to turn away: A writer is no detached judge of his countrymen and contemporaries; he is an accomplice to all the evils committed…

“…what can literature possibly do against the ruthless onslaught of open violence? … violence does not live alone and is not capable of living alone: it is necessarily interwoven with lies.….

“The simple act of an ordinary brave person is not to participate in lies, not to support false actions, His rule: Let THAT enter the world, let it even reign supreme – but not through me.….

“…but it is within the power of writers and artists to do much more: to defeat the lie! For in the struggle with lies, art has always triumphed and shall always triumph! Visibly, irrefutably and for all! Lies can prevail against much in this world, but never against art…”

“…..One word of truth will outweigh the whole world.” (12)

Shortly after reading Solzhenitsyn’s words, I saw the power of art demonstrated by Saudi artist, Abdulnasser Gharem, through his brave and impressive artwork at the Basel Art Expo last year titled “The Safe” which alludes to the death of journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

There was nothing to point you to Gharem’s masterpiece in the Expo hall except a long queue curling back on itself while it shuffled steadily towards a huge white box, about the size of a shipping container, with a single entrance: a closed white door, under a rather plush, Georgian over door canopy, also an untainted white.

While inside one could privately contribute to the artwork by replicating the rubber stamp messages or pen your own in red ink.

Abdulnasser Gharem’s work inspires us to create new ways of seeing and feeling; so that we all step up a few notches and into the highest possible versions of ourselves.

The best film example I’ve seen recently, is a true story about fake news called Shock and Awe by Rob Reiner This film gives us a glimpse of the enormous hurdles journalists are up against in today’s world. It premiered at the Zurich film festival in 2017 and is a true story about journalists Jonathan Landay, Warren Strobel, John Walcott and Joe Galloway trying to stay in integrity and do justice to their craft against all odds, in the wake of 911 during the lead up to the war on Iraq. I think it’s a must watch for us today, particularly while we are in global lockdown. If there’s one thing we’ve all learnt in the last few months it’s not to take any information at face value, no matter how respected the source. The whole lockdown experience seems a tailor-designed phenomenon for each of us to each earn a PhD in fakes news, specifically how to tell the difference between our own and everyone else’s. (3)

But what about all the artists or writers who can never hope to make it into an art gallery let alone the Basel Expo or into a box office hit or the pages of prestigious magazines or publishing houses without selling their souls via social media or to whoever is paying the electricity bill? How can they follow Solzhenitsyn’s advice?

We will explore ideas on this later.

And what if you don’t feel inspired to create anything?

As mentioned before, there are two parts to Solzhenitsyn’s advice. And the second point is really just the tip of the iceberg.

The first part is: What action we can take right now as mere mortals (every one of us) to shift our lives in the right direction. We can come back into integrity with ourselves by taking note of, and clearing up, our own “fake news”. The real groundwork to be done by all of us. And we can practice not colluding in nor condoning or turning a blind eye to lies in order to get ahead. Let’s not forget, any work done with an open heart and genuine intention to help is love in action (4)Besides, great art doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It requires collaboration, support, publishers … “Every tiny screw, cog or spring is needed to make a clock.” Eileen Caddy (5)

Triumphing over expedience

Certainly, all of us need to find a way to survive, or feed our families and perhaps the only reason we are here today is because our ancestors grovelled, complied, obeyed, or sold their souls outright in order to belong and therefore stay alive or because they turned a blind eye or prostituted themselves in some large or small way for survival of themselves or their offspring. But do we need to still carry on this soul barter?

Solzhenitsyn says no. That the “…the meaning of earthly existence lies not, as we have grown used to thinking, in prospering, but…in the development of the soul. From that point of view our torturers have been punished most horribly of all: they are turning into swine, they are departing downwardly from humanity. From that point of view punishment is inflicted on those whose development..holds out hope.”

(Bwah! What a thought!)

A page further on Solzhenitsyn continues: [What I learnt from my prison years was] how a human being becomes evil and how good. In the intoxication of youthful successes I had felt myself to be infallible, and I was therefore cruel. In the surfeit of power I was a murderer, and an oppressor. In my most evil moments I was convinced that I was doing good, and I was well supplied with systematic arguments. And it was only when I lay there on rotting prison straw that I sensed within myself the first stirrings of good. Gradually it was disclosed to me that the line separating good and evil passes not through states or between classes, nor between political parties either — but right through every human heart — and through all human hearts. This line shifts. Inside us, it oscillates with the years. And even within hearts overwhelmed by evil, one small bridgehead of good is retained. And even in the best of all hearts, there remains…an uprooted small corner of evil. … it’s impossible to expel evil from the world in its entirety, but it is possible to constrict it within each person.” (6)

This sounds a bit like something Markus Hirzig said recently during a private call: “As soon as you realize that the whole game board is alive and responding to your every step, you make the next evolutionary jump. Your neighbors change. The game board expands.”

He spoke of this from an energetic perspective, adding that when we contract our energy due to fear from a younger period we literally make the game board smaller. “..and with millions contracting, the whole game board contracts

and we don’t have so many abilities anymore.

What was thinkable before (democracy, for example) is no longer thinkable.

We then have three choices says Hirzig: (2)

- to go with them and also contract (making the game board even smaller.)

- to leave/ not go along with them (through disassociation for example) and therefore also make the game board smaller(!!)

- Or we have a third choice. which is to stay fully present but not contract with them through fear or shame or anger. Then we have the possibility to look around clearly and see what the next adjacent possibility is? What agency do I have? What’s there for me to do? (2)

So, knowing all this, why do I still feel frozen regarding taking action?

Starting where you are now

In his article, Turning toward our blind spot: seeing the shadow as a source for transformation Otto Scharmer writes that required action depends on where we are in our own process.

Scharmer points to a turning point in global consciousness, like the last straw that broke the camel’s back: “Something changed when we all watched the same images — 8 minutes and 46 seconds — the killing of George Floyd. During that unbearable experience, something broke down and broke open in our hearts, in how we relate to one another, and in how we want to live together.”

Says Scharmer, “What is ours and what is mine to do? How can I contribute to the pathway that we are building together?

Answering these questions may require us to look in the mirror at our individual and collective shadow and ask:

What am I not seeing? (Where is my view distorted by a frozen mind?)

What am I not feeling? (Where is my sensing distorted by a frozen heart?)

What action, grounded in this deep seeing and sensing, am I not co-initiating yet? (Where are my actions distorted by a frozen will?) (1)

This is what I’m working on at the moment. Noticing when I’m distracted, or numb or the degree to which my heart is still closed…

A couple of years ago a friend sent me a video and later some books by Japanese/American artist Makoto Fujimura. I’ve watched this video a number of times and have shared it with many friends and clients. It’s an empowering message about culture care, about seeing “the gift” versus seeing everything in the world as a commodity. Like S’s message, about what we can each do, Fujimura talks about winter and preparing the soil for future generations. And this is exactly what art asks of us…and needs from us. Feeling what needs to be felt. And freeing this energy so that it can be repurposed. This is what our generations can and must do now.

Here is his empowering message to artists regarding expedience and what to do about culture care and honoring one’s “gift” in a world that sees everything as a commodity.

Fujimura echoes Solzhenitsyn when he says that the real power of art, literature, dance, poetry “is to help one climb into someone else’s skin and walk around… it helps us develop our empathic capacities; to be other-centred rather than self-centered.”

But he also points to art and culture’s current decay. Fujimura mentions the work of TS Eliot between the wars and of Ralph Ellison, author of The Innocent Man, who said, “If the word has the potency to revive and make us free, it also has the power to blind, imprison and destroy.” Ralph Ellison

Fujimura asks, “Is it possible that in the beginning of the 21 century art has missed something? …Has art been imprisoned?…Have we forgotten art’s potency to revive and set us free?”

“What is happening in our culture when a scientist cannot be a scientist, when an artist can’t be an artist? There’s something wrong”

“…Can art be part of the effort to set us free?” (30 min into video)

” The artist appeals to that part of our being which is a gift and not an acquisition…and therefore more permanently enduring.” Joseph Conrad.

We have forgotten our gift. Or misused it. (8)

Fujimura’s advice: (refers to the book The Gift by Lewis Hyde)

“When the native Americans managed the waters they took the salmon as a gift…

Western forces came in and treated it like a commodity.”

“[Nature] is a gift. Culture is a gift…Always do work that is not going to be sold or published. Let it be a gift to the world…there’s magic to this. Give what has been given to you, deeper intuitive layers of love that the you have tapped into. That first love is so intoxicating. People say you can’t be an artist and you cannot stop. You know there is a reality you must serve and so you write, at 3 am without anyone knowing that you are writing poetry…

“Emily Dickinson took care of her garden…few people knew she was writing..”

Fujimura continues:

(41.40 into the video) “Emily’s desk was only 17.5 x 17.5 inches. I tell younger writers, that’s all you need but you have to dedicate yourself to that space. Do not let anything else go on at that table. Let your being remain on that space so you always have a place to go home to. You can always be inspired to write the last paragraph, last stanza of a poem even though you are coming back at 2 am in the morning. You are vice precedent of general foods…and have to get up at 5am you still write.”

“..…[Dickinson] was a gardener and knew a good bulb sometimes takes years to take root. If the soil conditions aren’t right or winter is coming good seeds will wait. She buried her poems into the soil trusting they would come out when the time is right.”

She wrote as if she was writing as a gift to us today.”

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn also wrote as a gift to others. When he had nothing to write on he memorized his work by structuring it as rhyming poetry. Victor Frankl, Auschwitz survivor and author of Man’s Search for Meaning also wrote for future generations. So did many others. They wrote as a gift to us today. Let’s open and unpack their gift now rather than postpone humanity’s blossoming until another season, century or species picks up from where we are now.

Preparing the soil

And if we feel we have no seeds to sow and we think winter is coming, what can we do?

We can prepare the soil for future generations.

How can we do this? This is the work of Thomas Huebl, Otto Scharmer, Porges, Peter Levine, Michael Brown, Judith Kravitz and many others all working in the field of digesting collective trauma.

We can digest what needs to be digested after two world wars and a lot more. While there’s work to be done on a collective level there’s also work that can be done on a personal level.

As one of Scharmer’s students put it: everything in your life has prepared you for this moment in history.

Without truth we can’t have democracy.

We can take Solzhenitsyn’s advice: see the mirror, reflect on our own lives and clear up our own personal toxic waste and come back into alignment with ourselves and our inner calling. We can do our own private “truth and reconciliation” process and write or share about our own experiences, even if only for ourselves or our close family. And we can not support lies and corruption on any level, particularly in our leaders or companies. This calls for a maturing in each of us that is quite difficult to see and requires reaching out for help to see our own blind spots. (1)

Today we are at a crossroads. One path leads towards a totalitarian possibility the likes of which we have never seen before. The other path leads to the flowering of humanity, through the renaissance and transformation through how we relate to our environment and each other on every level. (13)

Which path do you choose?

This is what I plan to do. Start from the inside out. Crack open my own heart and reach for the higher ground, and in so doing perhaps inspire others to do likewise.

And look towards art from others for inspiration, like this beautiful love poem to our Earth from Lindi Nolte, to keep our eye on the stars instead of the mud below.

“ The future is not somewhere we go to, it’s what we bring here now.” Thomas Huebl

Notes plus resources

Some resources I have found useful:

1. Otto Scharmer: Turning Toward Our Blind Spot: Seeing the Shadow as a Source for Transformation

2. The work of Markus Hirzig and Thomas Huebl on this topic see the pocket project and the forthcoming collective trauma summit. Markus Hirzig on fakes news

3. Ken Wilbur on this topic: “Everyone has a unique perception of what the collective shadow actually is — whether it’s systemic racism, media manipulation, or top-down statist oppression — and when we feel like we are trying to confront that collective shadow, it gives us a sense of righteous purpose which, if we’re not careful, can become its own source of fresh shadow material for us to work with, because in the end it is very difficult to tell where your personal shadow ends and the collective shadow begins. Which means that when we think we are confronting a “collective shadow”, we are oftentimes just projecting our own shadow onto the world around us — our own fear, our own bias, our own powerlessness, our own need for certainty.” Wilbur on integrating shadow

4 For more on “preparing the soil” what else can we do personally, see Findhorn’s recent Rooots of tomorrow online sharing of their three core principles (How each of us can help the whole): co-creation with nature, inner listening and work as love in action. In other words, seeing the magic and mystery in the world we live in and learning to collaborate with this force is essential now more than ever before.

5. Quote from Eileen Caddy, Opening doors within. 365 daily meditations. August 14. see also August 25.

6. Quote from Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, for full quote and context see The Gulag Archipelago, Part IV, chapter 1 The Ascent, Vintage Abridged edition 2018, page 310-312

Some useful books related to this discussion

7. See also Rutger Bregman’s chapter on the best remedy for hate, injustice and prejudice. Which is also relational: what dissolves these feelings is contact. Humankind: a Hopeful History by Rutger Bregman, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020. (p. 347)

see also

TheoryU by Otto Scharmer

Freedom by Jeremy Griffith

Big Magic by Elizabeth Gilbert re doing other work on the side to keep your integrity.

Be Still by Winslow Eliot re inner stillness

On writing by Stephen King re “downloading inspiration for stories”

The Gift, by Lewis Hyde: art is a gift not a commodity.

Sula by Toni Morrison as a wonderful example of allowing another see the world through your eyes.

Brave New Word by Aldous Huxley

Scroll down in the link above for

Comparisons with George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four

8. What about Propaganda art?

Fujimura looks at where we are now, in our “death of culture”, but he doesn’t point to the individual choices, moment to moment, that Solzhenitsyn points to.

For example, many artists and writers, in an attempt to earn a living through their craft, have done time in the trenches of the advertising industry, me included. This art form, the art of persuasion, ranges from extreme forms of propaganda art enticing you to work in bomb factories or to be cannon fodder during two world wars, or more subtly today, to buy into someone else’s agenda, through high budget fake news. On the other end of the spectrum there’s the less harmful variant, so common now its the new normal: our current daily avalanche of inspirational emails inspiring you to “buy my stuff” or someone else’s stuff. As the boundaries blur, can we distinguish between transcendental, experiential art and persuasive art? The former gives you an opportunity to go to hell (virtually) with someone else and have a deeply emotional empathic experience and in the process, perhaps even your own epiphany, and the latter persuades you to go all the way to hell yourself, by first emptying your pockets or filling them up, in order to speed your descent?

When Solzhenitsyn spoke about literature he did not mean all forms of self expression. “If you express yourself, and scribble whatever you like, or some detective story, that’s not enough..Literature is above all responsible to God and all mankind.”

Source: Trilogy 1 – Live not by lies. (28 minutes into video).

There is so much fake news out there designed to persuade you and this is now becoming a science as well as an art, with high tech algorithms monitoring our behavior and choices 24/7.

This is why it’s important that we pay attention to Solzhenitsyn’s message now; to avoid taking the path that leads towards the slippery slope: from narcissism, expediency and air brushing of facts towards corruption of ourselves, of society and our leaders and eventually a high tech totalitarian regime. (see note 13 for more on this.)

From an “Art triumphing over lies” perspective, I loved the recent comedy-human drama study on this topic called JoJo Rabbit, about a few young and old victims of Nazi propaganda by New Zealand director Taika Waititi, based on Christine Leunen’s 2008 novel Caging Skies. (Waititi shows how easily brainwashing can happen to all of us and explores also how contact helps dissolve prejudice.) From a psychological perspective propaganda art is a whole study in itself. Rutger Bregman touches on this in his 2020 book, Humankind: a Hopeful History. He explores brainwashing, friendship and other factors in Part 3.

Here’s an article with lots of examples of Propaganda art. Interestingly, many of these people revolutionized graphic design and later had a change of heart. Perhaps “fake news” in the form of using our gift for the wrong cause is an early developmental stage that many of us go through in one way or another? (Maybe one day I’ll do some self reflection and write about this topic based on my own “sins” against my conscience.)

9. Further appreciation and recognition:

Thanks to two friends, Danie Hulett (student of Thomas Huebl and Markus Hirzig) and artist Joanina Pastoll, for their suggested amendments to an earlier draft.

The generous sharing of a summit hosted by the coaches rising team

and the generous sharing of Life’s work of Brian Johnson of Optimize.me

10. Remembering lives lost

Remembering musician Jimi Hendrix and all the other artists of the world who got too popular for their own good.

Remembering Homero Gómez and Raúl Hernández Romero – Mexican butterfly activists and so many other environmental activists in a time calling us to all stand up for nature and the planet of which we are part.

Remembering journalist Jamal Khashoggi and so many others. see also the website Reporters Without Borders

And honoring all journalists who stay true to their craft, like Jonathan Landay, Warren Strobel, John Walcott and Joe Galloway

Remembering all the lives cut short by police brutality, from the highly gifted South African activist Steve Biko during Apartheid years to the recent killing of George Floyd and so many more worldwide over the millennia.

12. Solzhenitsyn’s Writing

The Solzhenitsyn center, looked after by his family, has lots of resources, including an archive of images, a video library and a collection of his articles and speeches. Access here: solzhenitsyncenter.org

Solzhenitsyn’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech

Solzhenitsyn won the Nobel prize for literature in 1970 for his novel “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich“. He first accepted the Nobel award in 1970 in absentia in order to avoid expulsion. Eventually he also accepted it in person in December 1974 Some images from this event. Archival film footage is available on the same site in Trilogy 1 – Live not by lies.

The Gulag Archipelago was written later, while Solzhenitsyn was in exile in the West.

Solzhenitsyn’s Nobel speech is something we all need to read now because we are at the crossroads, a major turning point for humanity. One path leads towards regression and totalitarianism. The other path leads towards a renaissance and global transformation. His insight then can help us now.

A longer extract of the 1970 version is below. Source: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1970/solzhenitsyn/lecture/

For a better translation see the full 1972 version published on solzhenitsyncenter.org

13. Every piece of potentially fake news provides an opportunity for us to examine how we react, in a world that challenges us to see the difference between our own person shadow and the collective shadow. Our own fake news and others’. Can we reach for tools that help us “trust our own crooked eye” by noticing our own eye’s blind spot?

We can practice Scharmer’s exercises discussed in his article (note 1) or Markus Hirzig’s suggestion (discussed in note 2) by asking ourselves: Which of the three ways of responding do I personally default to?

– do I automatically contract/regress to a younger age, by feeling fearful and therefore frozen or unable to reach out or do I react rather than respond, such as get angry? If so, what age do I feel?

or

– do I withdraw my attention and leave (think instead of feel/dissociation)?

or

– do I stay present and not contract in fear but instead consider my options or possibilities: what action could I take if some of these circumstances turn out to be true?

or as Solzhenitsyn puts it: “Do not believe your brother, believe your own crooked eye.”

How can we use art, our experience of our world, seen through our own “crooked eye” to communicate this fundamental choice?